Patient Resources

Our Health Library information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Please be advised that this information is made available to assist our patients to learn more about their health. Our providers may not see and/or treat all topics found herein.

Topic Contents

- General Information About AIDS-Related Lymphoma

- Cellular Classification of AIDS-Related Lymphoma

- Stage Information for AIDS-Related Lymphoma

- Treatment Option Overview for AIDS-Related Lymphoma

- Treatment of AIDS-Related Peripheral / Systemic Lymphoma

- Treatment of AIDS-Related Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma

- Latest Updates to This Summary (09 / 18 / 2024)

- About This PDQ Summary

AIDS-Related Lymphoma Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]

This information is produced and provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The information in this topic may have changed since it was written. For the most current information, contact the National Cancer Institute via the Internet web site at http://cancer.gov or call 1-800-4-CANCER.

General Information About AIDS-Related Lymphoma

Background and Definitions

AIDS was first described in 1981, and the first definitions included certain opportunistic infections, Kaposi sarcoma, and central nervous system (CNS) lymphomas. In 1984, a multicenter study described the clinical spectrum of non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) in the populations at risk of AIDS.[1] The incidence of NHL has increased in a course almost parallel to that of the AIDS epidemic and accounts for 2% to 3% of newly diagnosed AIDS cases.[2] Since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in the mid-1990s, the incidence of lymphomas has decreased, and outcomes have improved.[3] Higher CD4-positive T-lymphocyte (CD4) counts in the HAART era have been associated with a shift in histological diagnoses. The shift is away from primary effusion lymphoma and primary CNS lymphoma, which occur with the lowest CD4 counts, and toward histologies that occur at higher CD4 counts, such as Burkitt lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL).[4,5,6] In contrast to less-frequent incidences of all the lymphoproliferative disorders in the HAART era, the incidence rate of anal cancer has not changed.[7]

Histology

Pathologically, AIDS-related lymphomas comprise a narrow spectrum of histological types consisting almost exclusively of B-cell tumors of aggressive type. These include:

- Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (including B-cell immunoblastic lymphoma).

- Small noncleaved lymphoma, either Burkitt or Burkitt-like.

The HIV-associated lymphomas can be categorized as:

- Aggressive B-cell lymphoma (see above).

- Primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL).

- Primary effusion lymphoma.

- Plasmablastic multicentric Castleman disease.

- HL.

HIV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma

Multiple reviews of HL occurring in patients at risk of AIDS have been done;[8,9] however, HL is still not part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definition of AIDS because no clear demonstration of its increased incidence in conjunction with HIV has been shown, as is the case for aggressive NHL. The CDC, in conjunction with the San Francisco Department of Public Health, has reported a cohort study in which HIV-infected men had an excess risk that was attributable to the HIV infection in 19.3 cases of HL per 100,000 person-years and 224.9 cases of NHL per 100,000 person-years. Although this report found an excess incidence of HL in HIV-infected homosexual men, additional epidemiologic studies will be needed before the CDC will reconsider HL as an HIV-associated malignancy.[10]

HIV-associated HL presents in an aggressive fashion, often with extranodal or bone marrow involvement.[8,9,11] A distinctive feature of HIV-associated HL is the lesser frequency of mediastinal adenopathy compared with non–HIV-associated HL. Most patients in these series had either mixed cellularity or lymphocyte-depleted HL, expression of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated proteins in Reed-Sternberg cells, B symptoms, and a median CD4 lymphocyte count of 300/dL or lower.[12] In a retrospective multicenter review of 62 patients, those receiving HAART with chemotherapy had a 74% 2-year overall survival (OS) rate versus a 30% OS rate for those not receiving HAART (P < .001).[13][Level of evidence C1] Among 201 patients with classical HL and HIV positivity, the 2- to 5-year OS rate of 88% to 90% after treatment with ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine), or similar regimens, and HAART, was not significantly different from the OS rate of HIV-negative patients with newly diagnosed HL in two uncontrolled comparisons.[14,15][Level of evidence C3] These studies confirm that patients with HL who were treated with standard regimens and HAART have outcomes that are similar to those of the uninfected population.[16] Furthermore, immune function recovers over the course of 6 to 9 months after completion of chemotherapy.[15]

Primary effusion lymphoma

Primary effusion lymphoma has been associated with Kaposi sarcoma (KS)-associated herpesvirus (KSHV)/human herpes virus type 8 (HHV8).[17,18] Primary effusion lymphoma presents as a liquid phase spreading along serous membranes in the absence of masses or adenopathy.[17] In addition to HHV8, many cases are also associated with EBV. Extension of lymphoma from the effusion to underlying tissue may occur. A series of 20 patients, including 19 treated with modified infusional etoposide, vincristine, and doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide and prednisone (modEPOCH), had a 3-year cancer-specific survival rate of 47% and a median OS of 22 months.[19][Level of evidence C3]

Multicentric Castleman disease

The plasmablastic type of multicentric Castleman disease is also associated with a coinfection of KSHV/HHV8 and HIV.[20] Patients typically present with fever, night sweats, weight loss, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly. Patients may progress to primary effusion lymphoma or to plasmablastic or anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Anecdotal responses to the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab alone (along with HAART), have been reported.[21,22,23,24][Level of evidence C3] For a prospective cohort of 84 patients treated with rituximab for HIV and HHV8 multicentric Castleman disease, the 5-year rate of relapse-free survival was 82% (95% confidence interval [CI], 72%–92%), and all patients responded again to rituximab at relapse.[24][Level of evidence C2]

Incidence and Prevention

An international database of 48,000 HIV-seropositive individuals from the United States, Europe, and Australia found a 42% decline in the incidence of NHLs from 1997 to 1999 compared with the same incidences in 1992 to 1996, both for PCNSL and for systemic lymphoma.[25] The introduction of HAART is the proposed explanation for this decline.[26] The diagnosis of AIDS precedes the onset of NHL in approximately 50% of the patients; however, in the other half of the patients, the diagnosis of AIDS is made at the time of the diagnosis of NHL and HIV positivity.[3] The geographic distribution of these lymphomas is also similar to the geographic spread of AIDS. Unlike KS, which has a predilection for homosexual men and appears to be on the decline in incidence, all risk groups appear to have an excess number of NHLs; these risk groups include intravenous drug users and children of HIV-positive individuals.

Clinical Presentation

In general, the clinical setting and response to treatment of patients with AIDS-related lymphoma is very different from that of the non-HIV patients with lymphoma. The HIV-infected individual with aggressive lymphoma usually presents with advanced-stage disease that is frequently extranodal.[27]

Common extranodal sites include:

- Bone marrow.

- Liver.

- Meninges.

- Gastrointestinal tract.

Very unusual sites are also characteristic and include:

- Anus.

- Heart.

- Bile duct.

- Gingiva.

- Muscles.

The clinical course is more aggressive, and the disease is both more extensive and less responsive to chemotherapy. Immunodeficiency and cytopenias, common in these patients at the time of initial presentation, are exacerbated by the administration of chemotherapy. Treatment of the malignancy increases the risk of opportunistic infections, which further compromise the delivery of adequate treatment.

Prognosis and Survival

Prognoses of patients with AIDS-related lymphoma have been associated with:[28]

- Stage (i.e., extent of disease, extranodal involvement, lactate dehydrogenase level, and bone marrow involvement).

- Age.

- Severity of the underlying immunodeficiency (measured by CD4 lymphocyte count in peripheral blood).

- Performance status.

- Prior AIDS diagnosis (i.e., history of opportunistic infection or KS).

Patients with AIDS-related PCNSL appear to have more severe underlying HIV-related disease than do patients with systemic lymphoma. In one report, this severity was evidenced by patients with PCNSL who had a higher incidence of previously diagnosed AIDS (73% vs. 37%), lower median number of CD4 lymphocytes (30/dL vs. 189/dL), and a worse median survival time (2.5 months vs. 6.0 months).[29] This report also showed that patients with poor risk factors—defined as Karnofsky Performance Status score lower than 70%, history of previously diagnosed AIDS, and bone marrow involvement—had a median survival time of 4.0 months compared with patients in a good prognosis group who had none of these risk factors, and who had a median survival time of 11.3 months.

In another report (NIAID-ACTG-142), prognostic factors were evaluated in a group of 192 patients with newly diagnosed AIDS-related lymphoma who were randomly assigned to receive either low-dose methotrexate, bleomycin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dexamethasone (m-BACOD) or standard-dose m-BACOD with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor.[30] No differences existed between these two treatments in terms of efficacy for disease-free survival, median survival, or risk ratio for death.[30][Level of evidence A1] On multivariate analysis, factors associated with decreased survival included age older than 35 years, history of intravenous drug use, stage III or stage IV disease, and CD4 counts lower than 100 cells/mm3. The International Prognostic Index may also be predictive for survival.[31,32,33] In a multicenter cohort study of 203 patients, in a multivariable Cox model, response to HAART was independently associated with prolonged survival (relative hazard, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.16–0.62).[34][Level of evidence C2]

References:

- Ziegler JL, Beckstead JA, Volberding PA, et al.: Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in 90 homosexual men. Relation to generalized lymphadenopathy and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med 311 (9): 565-70, 1984.

- Rabkin CS, Yellin F: Cancer incidence in a population with a high prevalence of infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Natl Cancer Inst 86 (22): 1711-6, 1994.

- Noy A: Optimizing treatment of HIV-associated lymphoma. Blood 134 (17): 1385-1394, 2019.

- Little RF, Wilson WH: Update on the Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Therapy of AIDS-related Lymphoma. Curr Infect Dis Rep 5 (2): 176-184, 2003.

- Carbone A, Gloghini A: AIDS-related lymphomas: from pathogenesis to pathology. Br J Haematol 130 (5): 662-70, 2005.

- Gopal S, Patel MR, Yanik EL, et al.: Temporal trends in presentation and survival for HIV-associated lymphoma in the antiretroviral therapy era. J Natl Cancer Inst 105 (16): 1221-9, 2013.

- Piketty C, Selinger-Leneman H, Bouvier AM, et al.: Incidence of HIV-related anal cancer remains increased despite long-term combined antiretroviral treatment: results from the french hospital database on HIV. J Clin Oncol 30 (35): 4360-6, 2012.

- Spina M, Vaccher E, Nasti G, et al.: Human immunodeficiency virus-associated Hodgkin's disease. Semin Oncol 27 (4): 480-8, 2000.

- Thompson LD, Fisher SI, Chu WS, et al.: HIV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 45 cases. Am J Clin Pathol 121 (5): 727-38, 2004.

- Hessol NA, Katz MH, Liu JY, et al.: Increased incidence of Hodgkin disease in homosexual men with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med 117 (4): 309-11, 1992.

- Re A, Casari S, Cattaneo C, et al.: Hodgkin disease developing in patients infected by human immunodeficiency virus results in clinical features and a prognosis similar to those in patients with human immunodeficiency virus-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer 92 (11): 2739-45, 2001.

- Dolcetti R, Boiocchi M, Gloghini A, et al.: Pathogenetic and histogenetic features of HIV-associated Hodgkin's disease. Eur J Cancer 37 (10): 1276-87, 2001.

- Hentrich M, Maretta L, Chow KU, et al.: Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) improves survival in HIV-associated Hodgkin's disease: results of a multicenter study. Ann Oncol 17 (6): 914-9, 2006.

- Montoto S, Shaw K, Okosun J, et al.: HIV status does not influence outcome in patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma treated with chemotherapy using doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. J Clin Oncol 30 (33): 4111-6, 2012.

- Hentrich M, Berger M, Wyen C, et al.: Stage-adapted treatment of HIV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma: results of a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 30 (33): 4117-23, 2012.

- Kaplan LD: Management of HIV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma: how far we have come. J Clin Oncol 30 (33): 4056-8, 2012.

- Simonelli C, Spina M, Cinelli R, et al.: Clinical features and outcome of primary effusion lymphoma in HIV-infected patients: a single-institution study. J Clin Oncol 21 (21): 3948-54, 2003.

- Nador RG, Cesarman E, Chadburn A, et al.: Primary effusion lymphoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity associated with the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpes virus. Blood 88 (2): 645-56, 1996.

- Lurain K, Polizzotto MN, Aleman K, et al.: Viral, immunologic, and clinical features of primary effusion lymphoma. Blood 133 (16): 1753-1761, 2019.

- Bower M, Newsom-Davis T, Naresh K, et al.: Clinical Features and Outcome in HIV-Associated Multicentric Castleman's Disease. J Clin Oncol 29 (18): 2481-6, 2011.

- Goedert JJ: Multicentric Castleman disease: viral and cellular targets for intervention. Blood 102 (8): 2710-11, 2003.

- Uldrick TS, Polizzotto MN, Aleman K, et al.: Rituximab plus liposomal doxorubicin in HIV-infected patients with KSHV-associated multicentric Castleman disease. Blood 124 (24): 3544-52, 2014.

- Marcelin AG, Aaron L, Mateus C, et al.: Rituximab therapy for HIV-associated Castleman disease. Blood 102 (8): 2786-8, 2003.

- Pria AD, Pinato D, Roe J, et al.: Relapse of HHV8-positive multicentric Castleman disease following rituximab-based therapy in HIV-positive patients. Blood 129 (15): 2143-2147, 2017.

- International Collaboration on HIV and Cancer: Highly active antiretroviral therapy and incidence of cancer in human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults. J Natl Cancer Inst 92 (22): 1823-30, 2000.

- Stebbing J, Gazzard B, Mandalia S, et al.: Antiretroviral treatment regimens and immune parameters in the prevention of systemic AIDS-related non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 22 (11): 2177-83, 2004.

- Sparano JA: Clinical aspects and management of AIDS-related lymphoma. Eur J Cancer 37 (10): 1296-305, 2001.

- Bower M, Gazzard B, Mandalia S, et al.: A prognostic index for systemic AIDS-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Ann Intern Med 143 (4): 265-73, 2005.

- Levine AM, Sullivan-Halley J, Pike MC, et al.: Human immunodeficiency virus-related lymphoma. Prognostic factors predictive of survival. Cancer 68 (11): 2466-72, 1991.

- Kaplan LD, Straus DJ, Testa MA, et al.: Low-dose compared with standard-dose m-BACOD chemotherapy for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases AIDS Clinical Trials Group. N Engl J Med 336 (23): 1641-8, 1997.

- Navarro JT, Ribera JM, Oriol A, et al.: International prognostic index is the best prognostic factor for survival in patients with AIDS-related non-Hodgkin's lymphoma treated with CHOP. A multivariate study of 46 patients. Haematologica 83 (6): 508-13, 1998.

- Rossi G, Donisi A, Casari S, et al.: The International Prognostic Index can be used as a guide to treatment decisions regarding patients with human immunodeficiency virus-related systemic non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer 86 (11): 2391-7, 1999.

- Straus DJ, Huang J, Testa MA, et al.: Prognostic factors in the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus-associated non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: analysis of AIDS Clinical Trials Group protocol 142--low-dose versus standard-dose m-BACOD plus granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. J Clin Oncol 16 (11): 3601-6, 1998.

- Hoffmann C, Wolf E, Fätkenheuer G, et al.: Response to highly active antiretroviral therapy strongly predicts outcome in patients with AIDS-related lymphoma. AIDS 17 (10): 1521-9, 2003.

Cellular Classification of AIDS-Related Lymphoma

Pathologically, AIDS-related lymphomas comprise a narrow spectrum of histological types consisting almost exclusively of B-cell tumors of aggressive type. These include:

- Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (B-cell immunoblastic lymphoma).

- Small noncleaved lymphoma, either Burkitt or Burkitt-like.

AIDS-related lymphomas, though usually of B-cell origin as demonstrated by immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene rearrangement studies, have also been shown to be oligoclonal, polyclonal, and monoclonal in origin. Although HIV does not appear to have a direct etiologic role, HIV infection does lead to an altered immunologic milieu. HIV generally infects T lymphocytes with the loss of regulation function that leads to hypergammaglobulinemia and polyclonal B-cell hyperplasia. B cells are not the targets of HIV infection. Instead, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is thought to be at least a cofactor in the etiology of some of these lymphomas. The EBV genome has been detected in most patients with AIDS-related lymphomas; molecular analysis suggests that the cells were infected before clonal proliferation began.[1] The rare primary effusion lymphoma consistently harbors human herpes virus type 8 and frequently contains EBV.[2] HIV-related T-cell lymphomas have also been identified and appear to be associated with EBV infection.[3]

References:

- Thorley-Lawson DA, Gross A: Persistence of the Epstein-Barr virus and the origins of associated lymphomas. N Engl J Med 350 (13): 1328-37, 2004.

- Simonelli C, Spina M, Cinelli R, et al.: Clinical features and outcome of primary effusion lymphoma in HIV-infected patients: a single-institution study. J Clin Oncol 21 (21): 3948-54, 2003.

- Thomas JA, Cotter F, Hanby AM, et al.: Epstein-Barr virus-related oral T-cell lymphoma associated with human immunodeficiency virus immunosuppression. Blood 81 (12): 3350-6, 1993.

Stage Information for AIDS-Related Lymphoma

Although stage is important in selecting the treatment of patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) who do not have AIDS, most patients with AIDS-related lymphomas have far-advanced disease.

Staging Subclassification System

Lugano classification

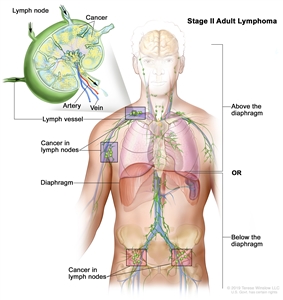

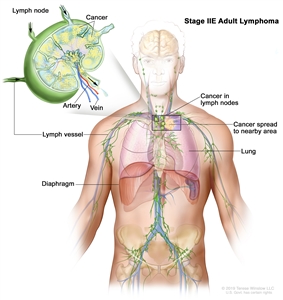

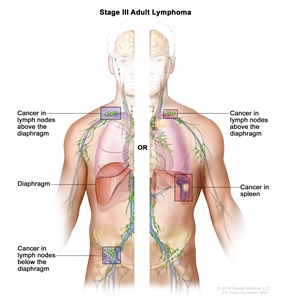

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) has adopted the Lugano classification to evaluate and stage lymphoma.[1] The Lugano classification system replaces the Ann Arbor classification system, which was adopted in 1971 at the Ann Arbor Conference,[2] with some modifications 18 years later from the Cotswolds meeting.[3,4]

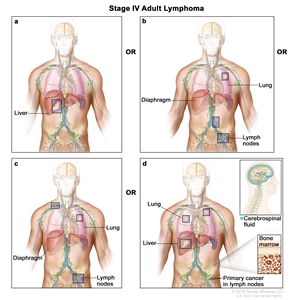

| Stage | Stage Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; CT = computed tomography; DLBCL = diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; NHL = non-Hodgkin lymphoma. | ||

| a Hodgkin and Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.:AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 937–58. | ||

| b Stage II bulky may be considered either early or advanced stage based on lymphoma histology and prognostic factors. | ||

| c The definition of disease bulk varies according to lymphoma histology. In the Lugano classification, bulk ln Hodgkin lymphoma is defined as a mass greater than one-third of the thoracic diameter on CT of the chest or a mass >10 cm. For NHL, the recommended definitions of bulk vary by lymphoma histology. In follicular lymphoma, 6 cm has been suggested based on the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index-2 and its validation. In DLBCL, cutoffs ranging from 5 cm to 10 cm have been used, although 10 cm is recommended. | ||

| Limited stage | ||

| I | Involvement of a single lymphatic site (i.e., nodal region, Waldeyer's ring, thymus, or spleen). |  |

| IE | Single extralymphatic site in the absence of nodal involvement (rare in Hodgkin lymphoma). | |

| II | Involvement of two or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm. |  |

| IIE | Contiguous extralymphatic extension from a nodal site with or without involvement of other lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm. |  |

| II bulkyb | Stage II with disease bulk.c | |

| Advanced stage | ||

| III | Involvement of lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm; nodes above the diaphragm with spleen involvement. |  |

| IV | Diffuse or disseminated involvement of one or more extralymphatic organs, with or without associated lymph node involvement; ornoncontiguous extralymphatic organ involvement in conjunction with nodal stage II disease; orany extralymphatic organ involvement in nodal stage III disease. Stage IV includesany involvement of the CSF, bone marrow, liver, or lungs (other than by direct extension in stage IIE disease). |  |

| Note: Hodgkin lymphoma uses A or B designation with stage group. A/B is no longer used in NHL. | ||

Occasionally, specialized staging systems are used. The physician should be aware of the system used in a specific report.

The E designation is used when extranodal lymphoid malignancies arise in tissues separate from, but near, the major lymphatic aggregates. Stage IV refers to disease that is diffusely spread throughout an extranodal site, such as the liver. If pathological proof of involvement of one or more extralymphatic sites has been documented, the symbol for the site of involvement, followed by a plus sign (+), is listed.

| N = nodes | H = liver | L = lung | M = marrow |

| S = spleen | P = pleura | O = bone | D = skin |

Current practice assigns a clinical stage (CS) based on the findings of the clinical evaluation and a pathological stage (PS) based on the findings made as a result of invasive procedures beyond the initial biopsy.

For example, on percutaneous biopsy, a patient with inguinal adenopathy and a positive lymphangiogram without systemic symptoms might be found to have involvement of the liver and bone marrow. The precise stage of such a patient would be CS IIA, PS IVA(H+)(M+).

A number of other factors that are not included in the above staging system are important for the staging and prognosis of patients with NHL. These factors include:

- Age.

- Performance status (PS).

- Tumor size.

- Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) values.

- The number of extranodal sites.

References:

- Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp. 937–58.

- Carbone PP, Kaplan HS, Musshoff K, et al.: Report of the Committee on Hodgkin's Disease Staging Classification. Cancer Res 31 (11): 1860-1, 1971.

- Lister TA, Crowther D, Sutcliffe SB, et al.: Report of a committee convened to discuss the evaluation and staging of patients with Hodgkin's disease: Cotswolds meeting. J Clin Oncol 7 (11): 1630-6, 1989.

- National Cancer Institute sponsored study of classifications of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: summary and description of a working formulation for clinical usage. The Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Pathologic Classification Project. Cancer 49 (10): 2112-35, 1982.

Treatment Option Overview for AIDS-Related Lymphoma

The treatment of patients with AIDS-related lymphomas presents the challenge of integrating therapy appropriate for the stage and histological subset of malignant lymphoma with the limitations imposed by HIV infection.[1] In addition to antitumor therapy, essential components of an optimal non-Hodgkin lymphoma treatment strategy include:[2,3]

- Highly active antiretroviral therapy.

- Prophylaxis for opportunistic infections.

- Rapid recognition and treatment of intercurrent infections.

Patients with HIV positivity and underlying immunodeficiency have poor bone marrow reserve, which compromises the potential for drug dose intensity. Intercurrent opportunistic infection is a risk that may also lead to a decrease in drug delivery. Furthermore, chemotherapy itself compromises the immune system and increases the likelihood of opportunistic infection.

References:

- Levine AM: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related lymphoma: clinical aspects. Semin Oncol 27 (4): 442-53, 2000.

- Tirelli U, Bernardi D: Impact of HAART on the clinical management of AIDS-related cancers. Eur J Cancer 37 (10): 1320-4, 2001.

- Noy A: Optimizing treatment of HIV-associated lymphoma. Blood 134 (17): 1385-1394, 2019.

Treatment of AIDS-Related Peripheral / Systemic Lymphoma

The treatment of AIDS-related lymphomas involves overcoming several problems. These are all aggressive lymphomas, which by definition are diffuse large cell/immunoblastic lymphoma or small noncleaved cell lymphoma (Burkitt lymphoma). These lymphomas frequently involve the bone marrow and central nervous system (CNS) and, therefore, are usually in an advanced stage. In addition, the immunodeficiency of AIDS and the leukopenia that is commonly seen with HIV infection makes the use of immunosuppressive chemotherapy challenging.

The introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has led to a marked reduction in opportunistic infections, prolonged survival with HIV infection, and a median overall survival (OS) for patients with AIDS-related lymphoma that is comparable with the outcome in the nonimmunosuppressed population.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7][Level of evidence C3] The use of HAART has also allowed standard-dose and even intensive chemotherapy regimens to be given with reasonable safety to patients with AIDS-related lymphomas, which is comparable with the outcome in patients without HIV.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]

Several prospective nonrandomized trials and pooled individual data from 19 prospective trials that included 1,546 patients show that the addition of rituximab to combination chemotherapy improves the complete response rate, progression-free survival, and OS.[3,4,5,6][Level of evidence C3] Several other prospective nonrandomized trials and the pooled individual data from the same 1,546 patients also show that infusional EPOCH (infusional etoposide, infusional vincristine, infusional doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone) produced better outcomes than did CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) (hazard ratioOS, 0.33; P = .03).[3,6,7][Level of evidence C3] Concurrent use of HAART with the infusional EPOCH regimen is controversial; one group advocated for HAART after completion of chemotherapy,[7] while others allowed concurrent therapy.[6]

For patients with Burkitt lymphoma, dose-modified regimens such as R-CODOX (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, methotrexate, cytarabine and rituximab)-M/IVAC (ifosfamide, etoposide, and high-dose cytarabine) or R-EPOCH (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, and doxorubicin in combination with rituximab) have shown good results with concurrent or sequential HAART.[7,11,12]

Patients at risk of subsequent CNS involvement include those with bone marrow involvement or those with EBV identified in the primary tumor or in the cerebrospinal fluid (i.e., by polymerase chain reaction).[13,14] Intrathecal chemotherapy is usually considered for patients who are at higher risk of CNS involvement.

Highly selected patients with resistant or relapsed lymphoma after first-line chemotherapy and with continued responsiveness to HAART underwent second-line chemotherapy followed by high-dose therapy and autologous peripheral stem cell transplant. Long-term survivors have been reported anecdotally for these highly selected patients who relapsed.[15,16,17,18][Level of evidence C3]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- Mounier N, Spina M, Gabarre J, et al.: AIDS-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma: final analysis of 485 patients treated with risk-adapted intensive chemotherapy. Blood 107 (10): 3832-40, 2006.

- Weiss R, Mitrou P, Arasteh K, et al.: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related lymphoma: simultaneous treatment with combined cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone chemotherapy and highly active antiretroviral therapy is safe and improves survival--results of the German Multicenter Trial. Cancer 106 (7): 1560-8, 2006.

- Barta SK, Xue X, Wang D, et al.: Treatment factors affecting outcomes in HIV-associated non-Hodgkin lymphomas: a pooled analysis of 1546 patients. Blood 122 (19): 3251-62, 2013.

- Wyen C, Jensen B, Hentrich M, et al.: Treatment of AIDS-related lymphomas: rituximab is beneficial even in severely immunosuppressed patients. AIDS 26 (4): 457-64, 2012.

- Levine AM, Noy A, Lee JY, et al.: Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone in AIDS-related lymphoma: AIDS Malignancy Consortium Study 047. J Clin Oncol 31 (1): 58-64, 2013.

- Sparano JA, Lee JY, Kaplan LD, et al.: Rituximab plus concurrent infusional EPOCH chemotherapy is highly effective in HIV-associated B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 115 (15): 3008-16, 2010.

- Dunleavy K, Little RF, Pittaluga S, et al.: The role of tumor histogenesis, FDG-PET, and short-course EPOCH with dose-dense rituximab (SC-EPOCH-RR) in HIV-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 115 (15): 3017-24, 2010.

- Ratner L, Lee J, Tang S, et al.: Chemotherapy for human immunodeficiency virus-associated non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in combination with highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Oncol 19 (8): 2171-8, 2001.

- Wang ES, Straus DJ, Teruya-Feldstein J, et al.: Intensive chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, high-dose methotrexate/ifosfamide, etoposide, and high-dose cytarabine (CODOX-M/IVAC) for human immunodeficiency virus-associated Burkitt lymphoma. Cancer 98 (6): 1196-205, 2003.

- Cortes J, Thomas D, Rios A, et al.: Hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone and highly active antiretroviral therapy for patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia. Cancer 94 (5): 1492-9, 2002.

- Noy A: Optimizing treatment of HIV-associated lymphoma. Blood 134 (17): 1385-1394, 2019.

- Noy A, Kaplan L, Lee J: Feasibility and toxicity of a modified dose intensive R-CODOX-M/IVAC for HIV-associated Burkitt and atypical Burkitt lymphoma (BL): preliminary results of a prospective multicenter phase II trial of the AIDS Malignancy Consortium (AMC). [Abstract] Blood 114 (22): A-3673, 2009.

- Cingolani A, Gastaldi R, Fassone L, et al.: Epstein-Barr virus infection is predictive of CNS involvement in systemic AIDS-related non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. J Clin Oncol 18 (19): 3325-30, 2000.

- Scadden DT: Epstein-Barr virus, the CNS, and AIDS-related lymphomas: as close as flame to smoke. J Clin Oncol 18 (19): 3323-4, 2000.

- Re A, Michieli M, Casari S, et al.: High-dose therapy and autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation as salvage treatment for AIDS-related lymphoma: long-term results of the Italian Cooperative Group on AIDS and Tumors (GICAT) study with analysis of prognostic factors. Blood 114 (7): 1306-13, 2009.

- Krishnan A, Molina A, Zaia J, et al.: Durable remissions with autologous stem cell transplantation for high-risk HIV-associated lymphomas. Blood 105 (2): 874-8, 2005.

- Costello RT, Zerazhi H, Charbonnier A, et al.: Intensive sequential chemotherapy with hematopoietic growth factor support for non-Hodgkin lymphoma in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Cancer 100 (4): 667-76, 2004.

- Balsalobre P, Díez-Martín JL, Re A, et al.: Autologous stem-cell transplantation in patients with HIV-related lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 27 (13): 2192-8, 2009.

Treatment of AIDS-Related Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma

As with other AIDS-related lymphomas, primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma (PCNSL) is an aggressive B-cell neoplasm, either diffuse large B-cell or diffuse immunoblastic non-Hodgkin lymphoma (a subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma). AIDS-related PCNSL has been reported to have a 100% association with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).[1] These patients usually have evidence of low CD4-positive T lymphocyte counts, high HIV viral load, severe debilitation, and focal neurological symptoms such as seizures, changes in mental status, and paralysis.

Computed tomographic scans show contrast-enhancing mass lesions that may not always be distinguished from other CNS diseases, such as toxoplasmosis, that occur in patients with AIDS.[2] Magnetic resonance imaging studies using gadolinium contrast may be a more useful initial diagnostic tool in differentiating lymphoma from cerebral toxoplasmosis or progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Lymphoma tends to present with large lesions, which are enhanced by gadolinium. In cerebral toxoplasmosis, ring enhancement is very common, lesions tend to be smaller, and multiple lesions are seen.[3,4,5] Use of positron emission scanning has demonstrated an improved ability to distinguish PCNSL from toxoplasmosis.[6,7] PCNSL has an increased uptake while toxoplasmosis lesions are metabolically inactive. Antibodies against toxoplasmosis may also be very useful because most cerebral toxoplasmosis occurs as a consequence of reactivity of a previous infection. If the immunoglobulin G titer is less than 1:4, the disease is unlikely to be toxoplasmotic. A lumbar puncture may be useful to detect as many as 23% of patients with malignant cells in their cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Evaluating the CSF for EBV DNA may be a useful lymphoma-specific tool because EBV is present in all patients with PCNSL. Despite the many evaluations, however, most patients with PCNSL require a pathological diagnosis.[8,9,10] Diagnosis is made by biopsy. Sometimes, a biopsy is attempted only after failure of antibiotics for toxoplasmosis, which will produce clinical and radiographic improvement within 1 to 3 weeks in patients with cerebral toxoplasmosis.[11]

Radiation therapy alone has usually been used in this group of patients. With doses in the range of 35 Gy to 40 Gy, median duration of survival has been only 72 to 119 days.[2,12,13] Survival is longer in younger patients with better performance status and the absence of opportunistic infection.[14] In the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) era, a median survival of 18 months has been seen with radiation therapy alone.[15] An anecdotal report using HAART and high-dose methotrexate for patients with AIDS-related PCNSL showed a median survival that had not been reached with a median follow-up of 27 months.[16] Most patients respond to treatment by showing partial improvement in neurological symptoms. Autopsies have revealed that these patients die of opportunistic infections as well as tumor progression. Treatment of these patients is also complicated by other AIDS-related CNS infections, including subacute AIDS encephalitis, cytomegalovirus encephalitis, and toxoplasmosis encephalitis. Spontaneous remissions have been reported after HAART.[17]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References:

- MacMahon EM, Glass JD, Hayward SD, et al.: Epstein-Barr virus in AIDS-related primary central nervous system lymphoma. Lancet 338 (8773): 969-73, 1991.

- Goldstein JD, Dickson DW, Moser FG, et al.: Primary central nervous system lymphoma in acquired immune deficiency syndrome. A clinical and pathologic study with results of treatment with radiation. Cancer 67 (11): 2756-65, 1991.

- Nyberg DA, Federle MP: AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma and lymphomas. Semin Roentgenol 22 (1): 54-65, 1987.

- Fine HA, Mayer RJ: Primary central nervous system lymphoma. Ann Intern Med 119 (11): 1093-104, 1993.

- Ciricillo SF, Rosenblum ML: Use of CT and MR imaging to distinguish intracranial lesions and to define the need for biopsy in AIDS patients. J Neurosurg 73 (5): 720-4, 1990.

- Hoffman JM, Waskin HA, Schifter T, et al.: FDG-PET in differentiating lymphoma from nonmalignant central nervous system lesions in patients with AIDS. J Nucl Med 34 (4): 567-75, 1993.

- Pierce MA, Johnson MD, Maciunas RJ, et al.: Evaluating contrast-enhancing brain lesions in patients with AIDS by using positron emission tomography. Ann Intern Med 123 (8): 594-8, 1995.

- Cinque P, Brytting M, Vago L, et al.: Epstein-Barr virus DNA in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with AIDS-related primary lymphoma of the central nervous system. Lancet 342 (8868): 398-401, 1993.

- Cingolani A, De Luca A, Larocca LM, et al.: Minimally invasive diagnosis of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related primary central nervous system lymphoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 90 (5): 364-9, 1998.

- Yarchoan R, Jaffe ES, Little R: Diagnosing central nervous system lymphoma in the setting of AIDS: a step forward. J Natl Cancer Inst 90 (5): 346-7, 1998.

- Mathews C, Barba D, Fullerton SC: Early biopsy versus empiric treatment with delayed biopsy of non-responders in suspected HIV-associated cerebral toxoplasmosis: a decision analysis. AIDS 9 (11): 1243-50, 1995.

- Baumgartner JE, Rachlin JR, Beckstead JH, et al.: Primary central nervous system lymphomas: natural history and response to radiation therapy in 55 patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Neurosurg 73 (2): 206-11, 1990.

- Remick SC, Diamond C, Migliozzi JA, et al.: Primary central nervous system lymphoma in patients with and without the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. A retrospective analysis and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 69 (6): 345-60, 1990.

- Corn BW, Donahue BR, Rosenstock JG, et al.: Performance status and age as independent predictors of survival among AIDS patients with primary CNS lymphoma: a multivariate analysis of a multi-institutional experience. Cancer J Sci Am 3 (1): 52-6, 1997 Jan-Feb.

- Hoffmann C, Tabrizian S, Wolf E, et al.: Survival of AIDS patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma is dramatically improved by HAART-induced immune recovery. AIDS 15 (16): 2119-27, 2001.

- Gupta NK, Nolan A, Omuro A, et al.: Long-term survival in AIDS-related primary central nervous system lymphoma. Neuro Oncol 19 (1): 99-108, 2017.

- McGowan JP, Shah S: Long-term remission of AIDS-related primary central nervous system lymphoma associated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 12 (8): 952-4, 1998.

Latest Updates to This Summary (09 / 18 / 2024)

The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above.

Editorial changes were made to this summary.

This summary is written and maintained by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of NCI. The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or NIH. More information about summary policies and the role of the PDQ Editorial Boards in maintaining the PDQ summaries can be found on the About This PDQ Summary and PDQ® Cancer Information for Health Professionals pages.

About This PDQ Summary

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of AIDS-related lymphoma. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians in the care of their patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

Reviewers and Updates

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should:

- be discussed at a meeting,

- be cited with text, or

- replace or update an existing article that is already cited.

Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary.

The lead reviewers for AIDS-Related Lymphoma Treatment are:

- Eric J. Seifter, MD (Johns Hopkins University)

- Minh Tam Truong, MD (Boston University Medical Center)

Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's Email Us. Do not contact the individual Board Members with questions or comments about the summaries. Board members will not respond to individual inquiries.

Levels of Evidence

Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board uses a formal evidence ranking system in developing its level-of-evidence designations.

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as "NCI's PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary]."

The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Adult Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ AIDS-Related Lymphoma Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/lymphoma/hp/aids-related-treatment-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 26389186]

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in Visuals Online, a collection of over 2,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

Based on the strength of the available evidence, treatment options may be described as either "standard" or "under clinical evaluation." These classifications should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website's Email Us.

Last Revised: 2024-09-18

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Ignite Healthwise, LLC disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Learn how we develop our content.

Healthwise, Healthwise for every health decision, and the Healthwise logo are trademarks of Ignite Healthwise, LLC.